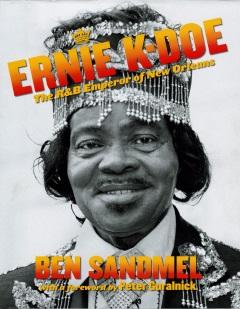

![]()

Ernie K-Doe . . . was an adored elder statesman of New Orleans music, a larger-than-life character, and usually an amiable host. The Mother-in-Law Lounge, which thrived in K-Doe’s image until 2010, was a place that filled visitors with giddy wonderment. Their delight ensued from the lounge’s welcoming environment and the surreal sensory overload that walloped all who crossed the threshold. This physical entrance doubled as the conceptual portal into Ernie K-Doe’s eccentric parallel universe—a festive, Fellini-esque realm where shameless idolatry and unfettered happiness reigned supreme. (“There’s a lot of love in here” was a frequent, typical reaction of first-time visitors.)

These intriguing enticements inspired many to bring their friends to the Mother-in-Law Lounge, for the pure fun of watching the newcomers’ enthrallment with this joyous, quirky little bar. The lounge’s hybrid ambience combined elements of a juke joint, a mosh pit, an R&B museum, and a cinematic set from Satyricon. It attracted a similarly eclectic clientele. Well-dressed, middle-aged black people bellied up to the bar alongside white street kids with torn jeans and bizarre piercings. Joining them were politicians seeking cultural credibility, off-duty cops, laborers in dirty work clothes, and fanatical R&B fans on pilgrimages to hallowed music sites around the South. A busload of blue-haired suburban ladies might turn up at any minute, stopping in for a nightcap after a casino gambling excursion. Birthday celebrants might likewise arrive en masse, sporting all manner of outrageous costumes. Derelicts and winos wandered in at times, receiving the same respect as well-heeled customers. The harmonious interactions of these diverse patrons affirmed them in the tradition of Huey P. Long’s credo “Every Man a King.” Or, as Ernie K-Doe often put it, “All you got to do is just keep the faith in what you are doing. You set your goal line, and don’t let nobody change you. You know what you say when people tell you you can’t do something? Fool, shut your mouth up!”

This resolute stance helped propel Ernie K-Doe through years of scuffling before “Mother-in-Law” hit the top. It also helped sustain him through the long, lean years after his star had faded. He nurtured himself during these tough times with glorious memories of May 1961, when “Mother-in-Law” became the best-selling record in America. The best-selling record in two Americas, actually—white and black—as delineated by Billboard magazine’s separate sales charts for pop and R&B. “Mother-in-Law” topped both charts, ruling pop’s Hot 100 for a single week and dominating the R&B survey for five. In pop it unseated Del Shannon’s “Runaway” and was in turn replaced by Ricky Nelson’s “Travelin’ Man.” (No other New Orleans artist, not even Fats Domino, had ever reached this peak with a song recorded in New Orleans. Domino, in fact, despite his frequent lofty chart positions and astronomical sales, never had a number-one record.) On the R&B side, “Mother-in-Law” displaced Ray Charles’s “One Mint Julep” and was bumped by Ben E. King’s “Stand by Me.” (Charles and K-Doe would compete again at the Grammy Awards, when Charles’s “Hit the Road Jack” was voted best R&B recording of1961, leaving “Mother-in-Law” as an also-ran.)

Compared to these hits and most others of the day, in both pop and R&B, “Mother-in-Law” has very blunt lyrics. . . . [Though tame] by contemporary standards, they raised eyebrows in the early ’60s, especially overseas. The English music weekly Melody Maker opined that “Mother-in-Law” “has made a big showing in the States—more, we feel, on account of its simple melodic appeal and rocking beat than the libellous sentiments it contains.” But London’s New Musical Express praised the song as “a cute comedy number in which Ernie tells his mother-in-law a few home truths about herself.”

If K-Doe’s disdainful sentiments in “Mother-in-Law” flirt with libel, his terse and deceptively cool delivery belie its caustic message. In New Orleans speak, this state of obvious annoyance—which, as alert observers realize, could imminently escalate into fireworks—is often telegraphed with the warning “You are working my last single nerve!” K-Doe’s ominously understated, last-single-nerve delivery is complemented by the sparse, less-is-more arrangement of producer Allen Toussaint. Toussaint, a New Orleans rhythm and blues savant who emerged as a major creative figure in American popular music, also plays piano on “Mother-in-Law.” His lilting solo echoes the Afro-Caribbean-influenced styles of such seminal New Orleans pianists as Jelly Roll Morton (Ferdinand LaMothe) and Professor Longhair (Henry Roeland Byrd). A century before “Mother-in-Law,” the same folk traditions had inspired the classical compositions of native son Louis Moreau Gottschalk.

“Mother-in-Law” was so popular that it inspired two “answer songs”: “Son-in-Law,” by the girl group the Blossoms, also recorded by Louise Brown (“the other day he even hocked her wedding ring”), and “Brother-in-Law (He’s a Moocher),” by rockabilly artist Paul Peek (“He’s lazy, won’t work, never had a job—get out of my house, you big fat slob”). “Mother-in-Law” is still considered a classic of overlapping genres, including R&B, pop, rock, and the loosely defined “beach music” of the Carolina coast. It has been reissued on at least a hundred anthologies and continues to get significant airplay on such diverse programs as Theme Time Radio Hour with Your Host Bob Dylan and American Routes with Nick Spitzer, and numerous oldies shows on R&B and pop stations. A multitude of new renditions continue to be recorded, including several Spanish-language versions, commonly titled “La Suegra.” In New Orleans, where the borders between musical genres are extremely porous, bands of every sort are asked to play “Mother-in-Law.” They’re expected to know it, along with K-Doe’s regional hits “T’aint It the Truth,” “Hello My Lover,” “Te Ta Te Ta Ta,” and “A Certain Girl.” None of these other fine songs achieved national success comparable to that of “Mother-in-Law,” but all are perpetual Gulf Coast favorites. Collectively they established the reputations of Ernie K-Doe and Allen Toussaint as masters of New Orleans rhythm and blues.

This was no small achievement at a time when that field was quite crowded. A vast surge of creativity and commercial success energized the Crescent City from the late 1940s to the early ’60s, an era later dubbed the golden age of New Orleans rhythm and blues. A cursory list of its other luminaries includes Fats Domino, Professor Longhair, Shirley and Lee, Smiley Lewis, Irma Thomas, Lee Dorsey, Lloyd Price, Art Neville, Aaron Neville, Huey “Piano” Smith, Frankie Ford, and Clarence “Frogman” Henry. The Meters and Dr. John, who emerged in the late ’60s, and the Neville Brothers (with siblings Aaron, Art, Charles, and Cyril), who formed a decade later, also stand in that illustrious number. So do the musicians who accompanied these artists on many of their records: saxophonists Lee Allen and Nat Perrilliat, drummers Earl Palmer and Smokey Johnson, bassists Frank Fields and Lloyd Lambert, and guitarists Roy Montrell, Justin Adams, and “Deacon” John Moore, to name but a few.

Ernie K-Doe felt thrilled when “Mother-in-Law” reached the top. He felt gratified decades later by its staying power. But he never ever felt surprised. “There ain’t but two songs that will stand the test of time,” K-Doe often declared. He would then pause at considerable dramatic length before naming them: “The first song is ‘The Star Spangled Banner,’ and the second song is ‘Mother-in-Law.’ Because people gonna have a mother-in-law until the end of the world.”

If K-Doe exaggerated his song’s importance, he did not overstate its broad, perpetual appeal. Negative depictions of mothers-in-law date back at least to the Roman satirist Juvenal: “Give up all hope of peace so long as your mother-in-law is alive.” Countless comedians, Henny Youngman for one, have echoed Juvenal’s sentiments: “I bought my mother-in-law a chair. Now they won’t let me plug it in.” And men are not alone in alleging persecution. The website www.motherinlawhell.com was created for “the daughter-in-law sisterhood . . . you are not alone. stop suffering in silence.” . . .

When the song hit number one, Ernie K-Doe became a respected peer of his R&B idols. He began performing at prestigious venues around America and in the Caribbean. He cast a significant shadow of musical influence over Europe, especially the nascent world of the British Invasion; in the UK his songs were covered by the likes of the Yardbirds and Herman’s Hermits. And he created a substantial and lasting legacy of top-notch rhythm and blues recordings. . . .

Ernie K-Doe recorded “Mother-in-Law” on April 25, 1960. But the song that would become his signature tune sat on the shelf for nearly a year before its release, and it almost wasn’t recorded at all. Accounts of the genesis of this epic number diverge on several key points. For the most part, K-Doe claimed to have written “Mother-in-Law” himself, referring to his grim experience with his own mother-in-law Lucy (or Lucifer, as he called her) as ample proof of authorship. Sometimes he simply cited Allen Toussaint as the writer, acknowledging, “There wouldn’t be no Ernie K-Doe if there wasn’t no Allen Toussaint.” In a third, more complex version, K-Doe claimed to have originated the concept and then coached Toussaint on how to get it down on paper . . .

Toussaint’s recollection includes no such collaboration, nor any real-life experience, on either K-Doe’s part or his own. “It was odd,” he told journalist Steve Wildsmith, “because I wasn’t married at the time, so I had no mother-in-law. It was just a joke used on television a lot in those days—‘Take my mother-in-law . . . please!’ [The song] was such a huge success, but it came from such an odd place.” . . .

Everyone involved with recording “Mother-in-Law” agreed that Toussaint hastily scrapped the song when K-Doe didn’t take to it immediately. Beyond this point of agreement, the narrative road quickly forks again. Toussaint has repeatedly stated that singer Willie Harper retrieved the song from the trash and persuaded Toussaint to try it again. K-Doe, of course, credited himself; who else would have had the prescience to rescue the creased and crumpled lead sheet from the wastebasket? “Don’t you never think,” K-Doe raved, “that I don’t know what I’m doing. I could make ’em or I could break ’em, I could throw ’em in the trash can and dig ’em out again like I did ‘Mother-in-Law’! Oh, that was a blessed day, that day I dug ‘Mother-in-Law’ out the trash can! It made Ernie K-Doe all over the world, and that’s why I’m Ernie K-Doe today!” Toussaint, with typical tact and forbearance, offered a differing account: “The story that ‘Mother-in-Law’ had gone in the trash is not fiction. But who pulled it out is fiction.” . . .

The Historic New Orleans Collection

The Historic New Orleans Collection